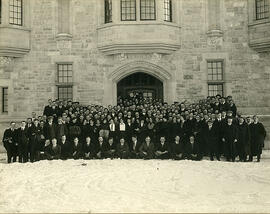

Saskatoon Normal School - Exterior

- A-8440

- Stuk

- 1969

View of Normal School with cars parked in front; winter scene.

Bio/Historical Note: The Saskatoon Teachers' College, originally called the Saskatoon Normal School, was a facility in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, for training teachers. The Saskatoon Normal School opened on 20 August 1912 in rented rooms in the Saskatoon Collegiate Institute (later Nutana Collegiate). It was a nondenominational institute for training primary and secondary school teachers. There were 12 second-class student teachers and 50 third-class students. Students also attended lectures at the University of Saskatchewan. The school moved in 1914 to four rooms rented in the Buena Vista School. In 1916 it moved again to rooms on the first floor of the university's Student's Residence No. 2. In 1919 the school moved again to St. Mary's separate school, and classrooms were also provided by the St. Thomas Presbyterian Church (now St. Thomas Wesley United Church). In 1920 it was decided to build a permanent home for the school on the west side of Saskatoon on Avenue A North. It was a gothic-style brick and Bedford stone building designed by architect Maurice W. Sharon and undertaken by architect David Webster. While construction was underway the school held classes in St. Paul's School on 22nd Street and 4th Avenue. The new school building was opened in March 1922, and the Provincial Normal School was officially opened on 12 February 1923, under the provincial Department of Education. In 1923 there were 335 students enrolled. In the summer of 1941 the Normal School gave up its building to the Defense Department for use in training air force recruits. The Normal School moved temporarily to Wilson School (on 7th Avenue North), whose students were relocated to other schools. It returned to the Avenue A premises after the end of World War II (1939–1945). The Normal School had an enrollment of 617 student teachers in 1945–46, of which three quarters were women. In 1953 the Normal School was renamed the Saskatoon Teacher's College. Teachers were now to be educated in teaching rather than trained in teaching. In 1986 the original Saskatoon Teachers College building was renamed the E.A. Davies building in honor of Fred Davies, a pioneer of technical education in Saskatchewan.