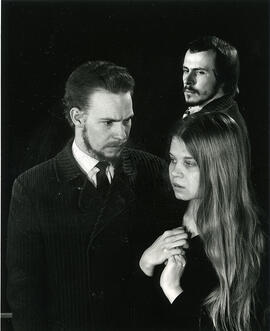

Greystone Theatre - "A Doctor In Spite of Himself"

- A-3657

- Item

- summer 1948

Murray Edwards (left), Frances Hyland, and two students in costume pose in front of a forest themed backdrop.

Bio/Historical Note: Frances Jean Hyland was born in 1927 in Shaunavon, Saskatchewan. She was raised by her mother's family in Ogema, Saskatchewan. Her mother put herself through teacher's college to support her daughter's acting career. Hyland graduated in 1948 from the University of Saskatchewan with a BA in English. She earned a scholarship to and graduated from the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London. After graduation Hyland made her professional debut in London in 1950, as Stella in A Streetcar Named Desire. In 1954 she returned to Canada to perform as Isabella in the Stratford Festival production of Shakespeare's Measure for Measure. She became a regular at the festival, performing in ten seasons. Her roles there included Isabella (in Measure for Measure), Portia (in The Merchant of Venice), Olivia (in Twelfth Night), Perdita (in The Winter's Tale), Desdemona (in Othello) and Ophelia in (in Hamlet). Hyland directed the Stratford Festival's 1979 production of Othello. She also performed with the Shaw Festival and on Broadway (opposite Tony Perkins in Look Homeward, Angel). On television Hyland co-starred on The Albertans and played Nanny Louisa on Road to Avonlea. Hyland was considered a champion of Canadian actors' campaign for higher status and pay. In 1970 Hyland was appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada. In 1994, Hyland received the Governor General's Performing Arts Award, Canada's highest honour in the performing arts, for her lifetime contribution to Canadian theatre. Frances Hyland died of respiratory failure following surgery in 2004.

![[Department of Drama] - "Wonderful Town"](/uploads/r/university-of-saskatchewan-archives/5/9/2/59228577ae9a7358fe21a09e380088c5e914640dbefdfb76c4683cf816575993/A-2572c_142.jpg)

![Greystone Theatre - ["Hamlet"]](/uploads/r/university-of-saskatchewan-archives/9/f/0/9f016d60760379e8be554176880415de714fd874f3e96caf5ada59005682af94/A-4956_142.jpg)